Insight into killing fields of England

The First World War may be high on the British agenda over the next year, but Michael Constantine has another war on his mind. Most working days, he drives down the A1 from his home in Sprotbrough, near Doncaster, to Newark, the Nottinghamshire market town where he is helping create Britain’s first centre devoted to the English Civil War.

The story of the National Civil War Centre, due to open in early 2015, has five significant Yorkshire connections, and Constantine’s is the strongest of them. He has an impressive pedigree in the county’s heritage industry; you’ve probably visited some of the places he has worked at over the past 20 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUntil 2008, he was at Brodsworth Hall, the “time-warped” Victorian country house on the outskirts of Doncaster that has been voted Britain’s favourite stately home. Much of the time he was curator, before becoming English Heritage’s assistant director in the North, then general manager of York’s Chocolate Story, the visitor attraction that explores one of the city’s major industries. And from there, he went just up the road to York Minster, where he took a strikingly new-broom approach.

As he drives me to the store where Newark’s unique Civil War collection is currently housed, he says that when he arrived at the Minster, some of its 300,000 annual visitors seemed confused as they walked through the doors.

“Unless you knew what you wanted to do, it was, ‘What do we do now? Do we pay?’ I got the staff to recognise the panic signs and explain it all.” They emerged from behind their desks to meet-and-greet.

So expect accessibility at the Civil War Centre, a £5.4m project backed by £3.5m from the Heritage Lottery Fund. It will, says Constantine, its business manager, “give people an extra reason to come to Newark”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdActually, there are plenty of good reasons already – a fine parish church, interesting medieval buildings, a vast and busy marketplace, in almost daily use for 500 years, plenty of antiques shops, and the castle, where King John died, famously from a “surfeit of peaches”.

Newark played a leading role in the Civil War. It was here in 1646 that Charles I surrendered to Scottish troops allied to the Roundheads. Royalist forces loyal to him were besieged three times here, before he ordered them too to surrender. The town had been protected by earthworks, now considered the most important to survive from the war.

And here’s the second Yorkshire Connection. Students from the University of Sheffield’s Archaeology Department are working on a bid for further Lottery funding for a community education project to excavate the earthworks. “They were last analysed in 1964,” says Glyn Hughes, curator of the Civil War Centre. “Technology has advanced so much since then that we can now get a much more accurate view of it.”

Other University of Sheffield students are researching Newark’s Civil War documents and maps, which survive, it’s thought, because plague broke out towards the end of the siege, deterring potential vandals from coming too close to the town.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe centre, which is taking shape in Grade II-listed former school buildings (Tudor, Georgian and Victorian) next to the town’s Palace Theatre, will have arms and armour on loan from the Royal Armouries in Leeds (third Yorkshire Connection). But it won’t, staff say, just be “all muskets and pikes”. It will focus on the everyday experience, the “human” stories of the war – in which Yorkshire, of course, played a key role, with castles under siege and, crucially, the 1644 Battle of Marston Moor, the scene of a crushing Royalist defeat and generally reckoned the largest battle ever fought on English soil.

“People know about the battles, but not what every Tom, Dick and Harry in the street was going through,” says Michael Constantine. “We have the best archive of the everyday life of the war: it’s not about the battles and the great and the good.”

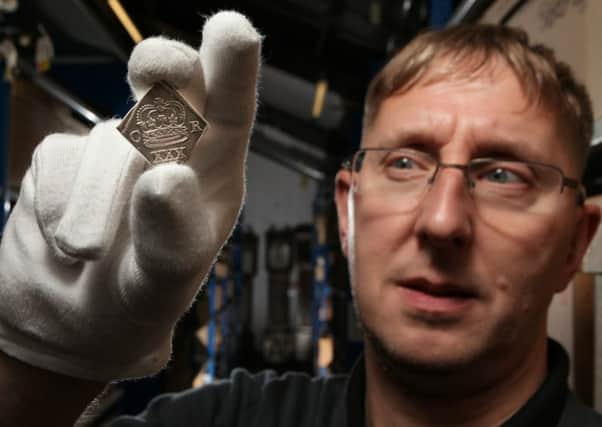

He delves in an envelope and eases out a “siege piece”, a lozenge-shaped silver token issued in lieu of money when the besieged town was sealed off from the outside world. Also in the archive are “touch pieces”, coins touched by the king which were superstitiously believed to cure disease.

“It’s the minutiae that are so fascinating,” says Glyn Hughes. “Like finding out how much the bell-ringers were paid when Queen Henrietta Maria – Charles I’s wife – came to Newark. You can relate to that.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany documents – bills, petitions, letters – that survived the war will be displayed in the evolving centre, which we tour, resplendent in hard hats. At the moment, it’s quite literally a building site, with floors taken up and beams waiting to be strengthened, but many intriguing details have come to light.

In a Tudor dormitory, names and dates have been scratched on the walls – R Disney 1608; WB Darwin 1790. Richard Darn, the project’s publicity officer, speculates that they may be forebears of more famous Disneys and Darwins.

For Darn, who lives in Barnsley (fourth Yorkshire Connection), the Civil War has a lingering relevance.

“It seems to go to the heart of the class differences between the aristocracy and the working man,” he says. It was, he adds, “a brutal conflict, not a gentlemen’s joust”.

The Civil War: A Yorkshire Gazeteer

Bolton Castle

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRoyalists holding this Wensleydale castle surrendered after a year-long siege reduced them to eating their horses. The Roundheads occupied it for two years before demolishing part of it.

Cawood

Besieged and re-besieged, Cawood castle, near Selby, was used as a prisoner-of-war camp by the victorious Roundheads before being largely destroyed after the Civil War ended. Its stone may have been used to build the Archbishop of York’s official residence.

Helmsley

The castle was besieged by the Roundheads under Sir Thomas (“Black Tom”) Fairfax in 1644. After the Royalists surrendered, much of its walls and gates, and part of its tower, were destroyed.

Knaresborough

The castle, a Royalist stronghold, was besieged by the Roundheads after their victory at Marston Moor. The Royalists surrendered, but a plan to demolish the castle was shelved after local petitions to use it as a prison.

Pontefract

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn January 1645, Cromwell’s cannon bombarded the Royalist-held castle for five days but, after 1,367 salvoes, only one tower had been destroyed. Eventually, after changing hands several times, it fell to the Roundheads.

Scarborough

The resort-to-be, a key supply port for the Royalists, changed hands regularly between 1642 and 1648. The Roundheads bombarded the castle from St Mary’s churchyard during a bloody five-month siege and the Royalists surrendered due to disease.

Sheffield

The castle was seized by the Roundheads in 1642, but was subsequently occupied by Royalists, who surrendered in 1644 after a siege. It was largely demolished in 1648.

Skipton

The castle, the last Royalist bastion in the North, fell to besieging Roundheads shortly before Christmas, 1645. Lady Anne Clifford stepped in to halt its demolition and restored it.

York

St Mary’s Tower, Marygate, was blown up by besieging Roundheads in 1644 but rebuilt after the Civil War, with a 17th century doorway transferred from King’s Manor.