How Britain became part of Second World War 80 years ago

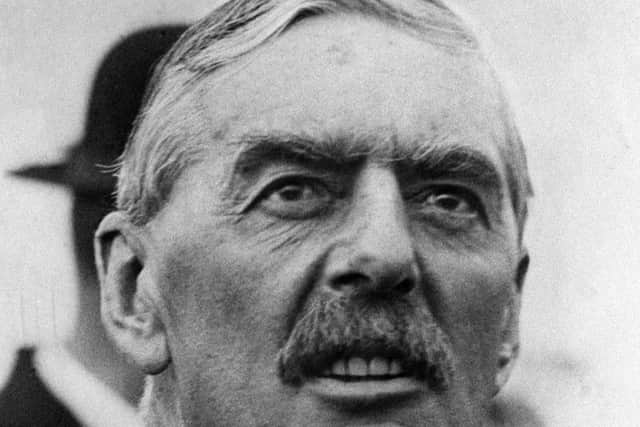

It was 11.15am on the morning of September 3, 1939, when the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, announced in a radio broadcast to the nation that the British deadline for the withdrawal of German troops from Poland had expired.

He said the British ambassador to Berlin had handed a final note to the German government stipulating that unless it announced plans to withdraw from Poland by 11am, a state of war would exist between the two countries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn sombre, stilted tones, Chamberlain continued: “I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received and consequently this country is at war with Germany.”

It was the news everyone had feared but expected, and so a mere 21 years after the guns fell silent on the Western Front, Britain once again found itself at war with Germany.

Chamberlain was desperate to avoid a repeat of the bloodbaths of the Somme and Passchendaele and staked everything on finding a diplomatic solution, and his inevitable failure to do so would lead to his political demise.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIronically, just as he had finished his broadcast the air raid sirens went off and Whitehall had to be evacuated. It proved to be a false alarm, though it was a sign that the world as they knew it was about to irrevocably change.

In the event, Britain and France barely lifted a finger to help Poland in its hour of need and by the end of September Polish resistance had been crushed as the country was sent back to a new dark age.

The same could be said of Europe. When Chamberlain returned from Munich in 1938, waving a piece of paper and proclaiming ‘peace in our time’ there was, briefly, hope that war could be averted.

However, when German troops marched into the Czech-held Sudetenland the following year it shattered any illusion that Hitler could be negotiated with, and all that remained was the dreadful realisation that they only way he would be stopped was by force.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was shock, too, at the non-aggression pact signed by Germany and the Soviet Union which preceded the invasion of Poland and left Britain and France isolated and vulnerable.Edward Spiers, Professor of Strategic Studies at the University of Leeds, says there was a sense of foreboding in the country 80 years ago.

“There was a sombre realisation that war had come again and people were braced for it,” he says.

There was a hive of activity as the country put itself on a war footing. Hospitals were cleared in case they were needed to cope with the expected air raid casualties. Some experts predicted there would be more than a million injuries in the space of two months.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There were more emergency laws passed in the first two weeks of the Second World War than in the entire first year of the First World War. So in a sense the government had learned from the past but people didn’t necessarily understand why these things were happening,” says Prof Spiers.

Unlike at the start of the First World War there was no great rush to sign up, instead men waited for their call up papers. There was, though, a rush to get married with August and September seeing the highest number of weddings ever recorded.

Still, in some ways little changed during those first few weeks in September. Families were encouraged to take advantage of the clement weather, with one advert for a coach company reading: “Don’t Mind Hitler, Take your holiday.” Cinemas were initially closed by the authorities only to reopen a few weeks later.

The introduction of the blackout was initially treated as a bit of a joke, but when the number of traffic incidents shot up it no longer seemed quite so funny. By the end of the first month of the war there had been 1,130 road deaths attributed to the blackout, with coroners urging pedestrians to carry a newspaper or a white handkerchief to make them more visible.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe biggest upheaval surrounded the evacuation of children out of cities which it was feared would be bombed by the Luftwaffe. Around 9,000 children had already been brought to the UK from Europe prior to the start of the war and now there was an even greater exodus.

“There was a significant amount of movement in the Phoney War period which differed depending on where you were,” says Prof Spiers. “There was a Government scheme and about four million adults and children were moved from the bigger cities, and another two million were evacuated privately.”

The first evacuees left on September 1 and over the course of the next few days more than 820,000 unaccompanied children and 524,000 with pre school youngsters left the cities, including places like Leeds, Hull and Sheffield.

“The irony was that by the early part of 1940 quite a large proportion of these had returned to their homes and there was a further exodus when the Blitz started. So there was a lot of upheaval.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Nick Evans, Lecturer in Diaspora History at the University of Hull, says people had read about what was happening in Poland and were fearful that they were next. “The day war broke out my great-grandmother got in her car and drove off with her youngest children to Wales because she was convinced that Hull would be bombed. So there was a real fear about what was coming.

“People were concerned about civilians being bombed, they were concerned about gas attacks, so there was the mass distribution of gas masks. Some of the terrors of the First World War were very much in the minds of those who were thinking about the conduct of the second.”

If there was a lot happening on the home front, it was a different story from a military point of view. “The first German bomb didn’t land on British soil until one was dropped on the Shetlands on the 13th of November and it’s not until December that the first British fatality is suffered in France. Compare that with the First World War, where 50,000 British servicemen had been lost in the first three months,” says Prof Spiers.

“France was our allie but it was beset with a defensive attitude. It built the Maginot Line and was sheltering behind that, and Britain wasn’t prepared to do any sort of bombing on Germany, not under Neville Chamberlain at least, for fear of reprisals.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was, however, no Phoney War at sea. “The liner Athenia was torpedoed within hours of war being declared and the Royal Oak battleship was sunk in October. So there was a war going on, just not on our doorstep.”

This was followed in December by the Battle of the River Plate off the coast of South America between three British warships and the German pocket battleship, the Admiral Graf Spee, which culminated in the latter being scuttled.

It was a welcome victory for the Navy and one the newly installed First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, was quick to jump on.This was, however, a rare piece of good news. The disastrous Norway Campaign in April 1940, which saw ill-equipped British troops sent packing, was the catalyst for the collapse of Chamberlain’s government, leaving the stage set for a new leader.

Eighty years ago, though, there was little talk, and even less hope, of the war being over by Christmas. And as families sat huddled around their wireless sets listening to Chamberlain’s voice crackle across the airwaves, the creeping sensation must have been one of dread.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was a sense of inevitability about another war in Europe during the 1930s, following the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany and Benito Mussolini in Italy, not to mention concerns surrounding the motives of Stalin’s Soviet Union.

Events took a downward spiral as the decade moved forward and Hitler’s increasingly aggressive foreign policy led to the invasion of the Czech lands (Bohemia and Moravia) in March 1939.

Britain and France subsequently agreed to support Poland in the event of a German invasion.

However, their agreement did little to deter Hitler, who attacked Poland on 1 September 1939. Two days later Britain declared war against Germany.