Why so many young people in Sheffield are getting tied up in knife crime – and what the community is doing to help

Anthony Olaseinde was 16 when he first saw somebody being stabbed. A group of young people had gotten into a fight at a fairground in Sheffield in 2005 – 18-year-old Jovan Bethune later passed away from his injuries.

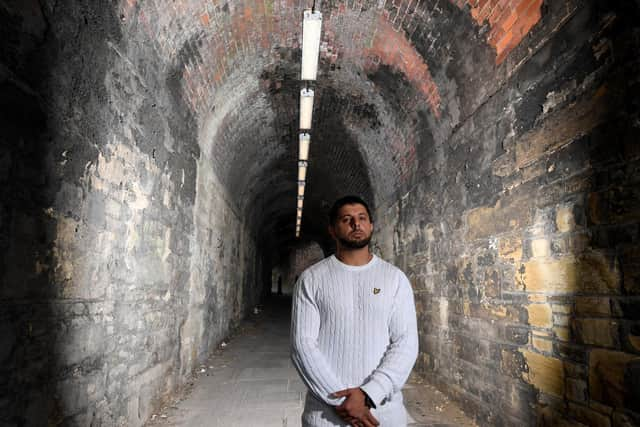

Now 32 and a father to two children himself, Mr Olaseinde runs the Keep Sheffield Stainless campaign and says knife crime is “spreading like wildfire” amongst young people in the city.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I have seen a lot of talking about ‘partnerships’ and ‘initiatives’ but I have not seen any improvement,” he says.

“We’re all trying to fight something that’s very hard to fight.”

Knife crime in the Steel City last year was nearly double the figures from just 2015. While the number of recorded incidents involving a knife has dropped slightly in the past two years, there were still 441 such crimes last year. In 2015, there were 271.

Figures from the Office of National Statistics released recently showed that, in South Yorkshire as a whole, there was an 11 per cent increase in possession of weapons offences between 2019 and 2020 from the year before.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA separate Freedom of Information request reveals that between March 2018 and 2019, there were 412 records of offences involving assaults and weapons in South Yorkshire schools and nurseries. Among the weapons seized are daggers, lock knives, knuckle dusters and even a machete.

Carrying weapons is cancerous, according to Sheffield’s community figures working with young people, who say the more violence children see, the more they are likely to carry a weapon to protect themselves. But in a cruel Catch-22, statistically you are three times more likely to be injured by your own weapon.

Hanif Mohammed is an ex-offender who was sentenced to 10 years in jail when he was 24 for manslaughter. Now at 37 he is Operations Manager at Sheffield’s In2Change, which supports young people and helps guide them away from crime, and last year appeared on Ross Kemp’s ITV documentary, Living With Knife Crime.

“It’s not comprehensible for most people why a child would carry a knife,” he tells The Yorkshire Post.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But put yourself in the position of a child where your father is in prison, you’re being bullied at school, your mother is on Universal Credit and you’re living in an area where violence occurs everyday.

“You want to have the same opportunities as everyone else, but you have no food and you’re not sleeping at night. This is a way of life for some people.

“I remember working with a young man who had been living in abject poverty. He had no money for food so instead he went out armed with a knife and would approach anyone who he saw was smartly dressed and looked like they had a bit of money, threatening them for cash. He never envisioned committing violence - it was an act of desperacy.

“Of course, we are all responsible for our own actions and I would never advocate any sort of crime. But that person was so desperate.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut the issue is not as clear cut as the need to protect yourself, both campaigners say. It is about children internalising and perpetuating stereotypes they are pigeon-holed into from birth.

“Kids just live out to be society’s expectations of them,” Mr Olaseinde says.

“They don’t know any different. If you raise a cat telling it every day that it’s a dog, it will think it’s a dog. When you’re from a certain area, you get tarred with a certain brush, especially if you are black or mixed race. It’s all about expectations of people.”

This is something echoed by Mr Mohammed, who is raw and honest about his experiences getting caught up in the world of gangs, drugs and violence at a young age.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe said: “I was very misguided when I was young. Crime was something very glamorous to me. I listened to music and watched films that glorified gangs and violence.”

By the age of 14, Mr Mohammed had been expelled from school and was exploited by a group of older boys who got him running around for them dealing drugs. The arrangement was working, until he lost money and it escalated into threats of violence against him and his family.

He then became involved in drug dealing for himself and, ultimately, was later convicted for his part in the killing of a man from Bradford.

“Prior to going to prison I wasn’t religious at all,” he adds. “I had been drinking and dealing drugs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There is a saying in Islam that if you save one person, it’s as if you’re saving all of humankind – that was my catalyst for change while in prison. Here we are 12 years later helping run an education centre.

“But my dream is not satisfied until politicians start listening and we really start to change what’s happening.”

And change is happening, slowly but surely.

South Yorkshire Police was one of the 18 police forces in the country identified as being worst-affected by violence last year, receiving £1.6m from the Home Office in October last year to set up its Violence Reduction Unit (VRU).

Joint head of the VRU Rachel Staniforth tells The Yorkshire Post they are taking the same approach to tackling and preventing violence as authorities take for public health issues, working directly with groups such as In2Change.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There are many complex reasons behind violence,” she says.

“Many of these young people we are reading about in media headlines - who have been arrested or a victim of violence - have been exploited, and it is something we will not tolerate.”

The young ages of suspects and victims is a common denominator in headlines. The day before speaking to Ms Staniforth, 17-year-old Emar Wiley is jailed for 16 years for the murder of 21-year-old Lewis Bagshaw in Southey, Sheffield.

The court heard how Wiley had become “desensitised” to violence, describing himself as “untouchable”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMs Staniforth adds: “But there are also individual factors which may have an impact, such as alcohol and substance abuse, whether it’s yourself or a family member.

“Other factors may be low income, living in deprived areas, domestic violence and poor quality housing. A lack of opportunities in life can make involvement in organised crime seem much more attractive.

“There is also a gender aspect, too. There is an idea that masculinity means defending your honour and standing up for yourself.”

Asked whether she agreed there was a connection between poverty and violence, Ms Staniforth said “absolutely”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Deprivation is a pre-cursor for all sorts of problems. That inequality in society is often what we talk about when it comes to public health issues.”

The VRU has contributed to 2,444 children and young people being educated about trauma, healthy relationships and domestic and sexual abuse, as well as 1,739 young people receiving direct interventions since its launch.

But while police efforts are becoming increasingly focused at working directly with communities to target the long-term causes of violence, is it enough on its own? Mr Mohammed does not think so.

“Culturally, it has always been cool to hate the police,” he said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“If a police officer is going into schools to talk to kids about knife crime, that’s great that awareness is being raised. But sadly they are not going to listen to an officer standing there in their uniform who hasn’t lived through what they live through.”

The In2Change centre receives no central funding, but despite this has managed to help thousands of young people in Sheffield re-find their path in life.

Equipped with a replica courtroom and prison cell, staff at In2Change help show people the real implications of carrying knives and getting involved with drugs, gangs and violence.

It is clear that young people need to see others who have grown up in the same neighbourhoods as them, who have seen the same problems and been caught in the same fights, and see that there is a way out that does not involve joining a gang or inflicting violence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I got told at school that I would end up in jail or dead,” Mr Olaseinde adds.

“ I got to the point where I thought, ‘I can be my own person, not what people expect me to be’.

Aged 23, he enrolled on a computer engineering course at Sheffield Hallam University. While studying, he set up his own security business before graduating with a First Class degree. He now has a book coming out called One Knife, Many Lives, and mentors in local schools.

Mr Mohammed, too, says it is “the messenger” that is important, not just the message.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I went to prison for ten years for killing someone. While I was in there, I realised, ‘I’m not an evil human being’.

“If somebody with my experience had come up to me when I was younger I would have really benefited from that.

“Young people of course have to show responsibility. Of course it’s not enough to say, ‘I grew up in a deprived area’. That’s not an excuse.

“But we have to recognise that for some children there are just a lot more obstacles in life.”