The Flying Scotsman: Meet the people who created and saved the national treasure

So the fortunate few in South Yorkshire who got their weekly wage from working in the relatively safe environment of the Carriageworks, adjacent to the Victorian station – yet to be rebuilt in a neo-Art Deco style – knew how lucky they were. No going down a dangerous pit for them. The works had been purpose-built in 1853 by the Great Northern Railway, which chose Doncaster because of the plentiful quantities of coal, steel and iron nearby. There was also a good supply of labour.

The site occupied about 200 acres of land, had 60 miles of sidings, and there were around 4,500 employees. Some of them, on that February day, must have given a little cheer when an entirely new design of train rolled out of the Plant, and onto the track alongside.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThose on the platforms would have been far more interested in the new livery of the LNER (London North East Railway), which had just been created by the amalgamation of dozens of smaller companies. LNER was a gigantic enterprise; of the new “big four”, it was second only in size to the London, Midland and Scottish. And LNER had just appointed an up-and-coming new designer, a young man called Nigel Gresley.

The locomotive emerging from the works was the first of many of his classic designs. It was numbered 1472, and records show that she cost just short of £8,000. She was a Pacific, an elegant piece of fine engineering, and would go on to have 77 sisters and half-sisters.

But then came the event that was to make her famous the world over. In 1924, as a boost to home morale and to show everyone else that Britain was still a force to be reckoned with, the British Empire Exhibition was held at Wembley. It was a showcase for everything that was great, good, and remarkable about the UK, its dominions and colonies.

When LNER was asked if it wanted to provide an exhibit, it offered its newest engine. The lovely 1472 was looked at by hundreds of thousands of visitors,who had no idea that she had been taken out of service for repairs. One of the small boys who stood in awe before her was a little lad from Retford, called Alan Pegler. He was just four years old.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen came a stroke of genius from someone in LNER’s publicity department. The company had been building what today we would call a "brand image”. It was an innovator in posters and in its advertising campaigns. LNER’s service between the English and the Scots capitals (it left King’s Cross every day at 10am precisely) had been known as “the Flying Scotsman” for some time, but how about, that anonymous bright spark reasoned, choosing one specific loco to carry the name?

She was taken back to Doncaster, and repainted. Gresley did not approve of the colour, a high-gloss apple green, but the great man’s opinions and protestations were totally ignored. She was then transported to Wembley, given her nameplates, and the nation’s love affair with Flying Scotsman began, and has endured for a century.

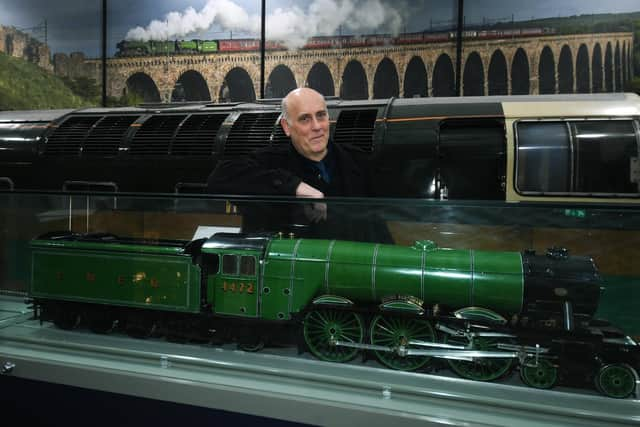

Bob Gwynne, associate curator of the the National Railway Museum (NRM), describes Flying Scotsman as “an icon, an equal to Big Ben or the Spitfire. She was the pinnacle of engineering of her day, but, 100 years on, she still has class, but combines that with somehow being a nostalgic symbol of a rather warm and friendly not-too-distant past, asimpler and a happier time. It’s strange but true – Scotsman has now been in preservation longer than she was in actual service.”

She is maintained today at an engineering works in Heywood, Greater Manchester, but her spiritual home is in the NRM in York – although there are many in Doncaster who believe that she should have her main “home” in the new city. The closest that they will get to Flying Scotsman in reality is when she passes through on the main line.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn her centenary year, there is a specially created exhibition at the NRM, and visitors will be able to see images of many of the colourful characters closely involved with Flying Scotsman. There was Alan Pegler, of course – a man so devoted to the green lady that he poured most of his fortune into her preservation, and who was made bankrupt as a result. She had been on a trip to the US, and was stranded.

Pegler could have declared his bankruptcy in the States but he realised that, if he did, the financial authorities would seize his assets. And the Flying Scotsman was one of them. So, the businessman – with hardly a penny to his name – wangled his return passage by boat, so that he could file for bankruptcy back home in the UK. In return for the voyage, he delivered lectures on the train to his fellow passengers.

She was rescued by Sir William McAlpine, who later confessed: “I never really felt that I owned it, I really believed that I held it in trust for people who loved it”. After Sir William, came millionaire and steam enthusiast Tony Marchington – incredibly, a photograph of the trio of Scotsman’s saviours has survived, the three men beaming into the camera lens. Ironically, they are standing in front of Mallard.

Scotsman was saved for the nation in 2004, when money was raised from several different sources. There was a lump sum from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, cash from Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Group, and – perhaps most significantly – over 6,500 donations from members of the public. “People just love her. In fact, ‘adoration’ is definitely not too strong a word,” says Gwynne.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlan Pegler was so devoted to the engine that, when he died, his ashes were scattered into her firebox as she sped along just outside Grantham – and up Stoke Bank. His daughter Penny Vaudoyer was on the footplate that day. Pegler knew the value of publicity – that’s why he took Scotsman to the US, and she has also visited Australia.

One of LNER’s “stars”, admired by small boys across the nation, was William “Bill” Sparshatt, a top link (most senior) driver. From 1931 to 1936, Sparshatt was the “face” of the Flying Scotsman service, and cheerfully posed (with gleaming oil can in hand) with many of the celebrities of the time. He had an enviable reputation for getting Scotsman to her destination on time, and he was also a dab hand at coaxing maximum speed from her. There’s a story that, when Sparshatt was climbing up on to the footplate one day, a rumour had gone round that a speed record was about to be set on the journey north. He would neither confirm nor deny the attempt, but gave the questioner the enigmatic answer that “if we hit anything today – we’ll hit it hard”.

Gresley knew what a fine driver Sparshatt was – and how fortunate that he was paired with fireman Webster. “They were all part of an extraordinary team, a jigsaw of characters who together make the main picture of Scotsman,” says Gwynne. “And perhaps the great thing of all was that Gresley was an innovator, an unashamed adapter of the ideas of others and open to outside influences. Together, they created a living legend.”

www.railwaymuseum.org.uk/flying-scotsman/centenary-programme