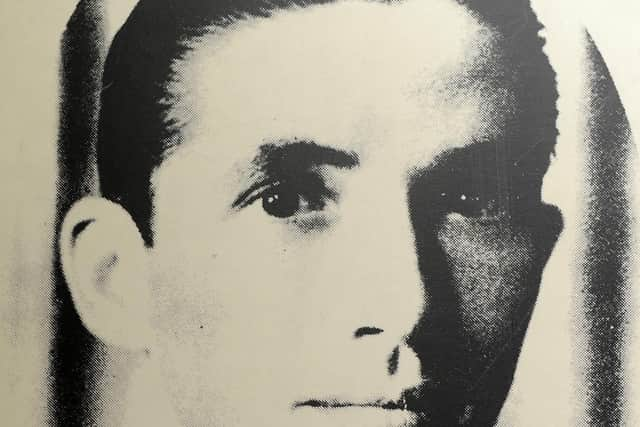

Ashley Jackson on the father he never knew - killed as a PoW by the Japanese in WW2

It signalled the end of the Second World War, but for Ashley Jackson’s family, and countless others, there was no such joy.

“There were a lot of mixed emotions because my father and my uncle had been captured and sent to Changi Prison in Singapore,” says Ashley. “We didn’t find out what happened to them until later on.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThough he has become synonymous with the Yorkshire landscape that his brooding watercolours capture so brilliantly, Ashley was actually born in Penang in Malaysia.

The Jackson family were living in Singapore, where his father Norman worked as general manager of the Tiger Beer Company, when the Second World War arrived unwanted on their doorstep.

By February 1942, the Japanese were rapidly closing in on what was then a strategic outpost of the British empire. Singapore, dubbed the “Gibraltar of the East”, had been regarded by the British military top brass as an impregnable fortress.

However, Norman Jackson, along with many others, didn’t share this confidence and with the net closing he arranged for Ashley and his mother, along with a whole host of aunts and uncles, to be put on board a ship bound for India.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He made sure the whole family got out. We were put on a ship and I remember my mum telling me later that we were on the deck of the ship and the Japanese planes were attacking the ships as they left the harbour. But thankfully we got away.”

Ashley was just 18 months old and it would prove to be the last time he saw his father who, as a Private in the Straits Settlements’ Volunteer Force, stayed behind to help defend Singapore.

Norman Jackson, along with Ashley’s grandfather and three of his uncles, was among the 100,000 British and Allied troops forced into captivity.

Over the years Ashley has pieced together a picture of him from a handful of photographs and documents that survived, along with the precious memories of family members.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe discovered, too, that during the 1930s his father travelled with a Japanese friend to Tokyo where they were arrested and accused of being spies. “They released my dad and he went back home but he never saw his friend again.”

It’s something Ashley believes meant his father’s card was marked when the Japanese later captured Singapore.

His father was sent to Changi Prison, one of the most notorious PoW camps used by the Japanese for forced labour. Some of the men were made to work in the docks where they loaded munitions on to ships, while others were forced to clear sewers damaged in the attack on Singapore. Those less fortunate were later sent to work on the infamous Burma railway.

Dysentery was rife and the men who were too ill to work had to rely on those who could for their food. Ashley’s father escaped from Changi several times and formed part of search and destroy teams before being recaptured.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAshley later met a PoW survivor who remembered his father. “He said he used to play the harmonica and played patriotic songs until the guards told him to stop playing them,” he says. “My dad spoke Japanese and Malay and I found out that he led some of the troops through the jungle after they escaped. They formed platoons and kept on fighting even when they were on the run.”

After one escape attempt too many, though, he was sent to another camp on the remote island of Labuan off the coast of Borneo. “He’d escaped five times and I think they’d had enough of him which is why they sent him there.”

And it was here where he met his tragic end. “My father was executed there with 25 other soldiers and one nurse,” says Ashley. “He was machine gunned into the grave with the others [each person was forced to dig their own grave]. We were told this was just 24 hours before the Australians liberated the camp.”

This was in June 1945, just a matter of weeks before the Japanese surrender.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNorman Jackson is named in the book Prisoners of the Emperor and is mentioned in the British War Museum. After many years of search and detailed assistance from the likes of the late John McAuley, who was a member of the National Malay and Borneo Veterans Association, Ashley was able to narrow down his father’s final resting place – he is among those buried in a British and Commonwealth cemetery on Labuan that contains the graves of 80 soldiers killed by the Japanese.

Decades later he made an emotional journey to the Far East visiting some of the places where his father was detained. “I got his name put on the cenotaph in Singapore and I made a pilgrimage to Changi jail. Outside there’s a little chapel where I left a message saying, ‘To my dad, Norman. Much regrets, love you – Ashley.’”

In 1995, he created a series of paintings of Penang for an exhibition at the Cooper Gallery in Barnsley which he dedicated to his father called Here’s to you Dad.

He still has letters from his father from the prison camp, a letter from George VI thanking him for his father’s service and most recently the presentation of medals that would have been given to his father for his service to King and Country. The latter was in 2015 when he contacted the Ministry of Defence Medal Office and received his father’s medals – 70 years after he was killed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It can never bring him back but it means that it is publicly recognised that he fought and died not just to protect my mum and I, but for King and Country,” he says.

Three years ago, his eldest granddaughter, Francesca, visited Norman’s grave. “She went to Labuan War Cemetery in Borneo to see his grave site and she took a letter that I had written to my father to his unmarked grave. It was both a proud moment that she had travelled alone on my behalf and also a poignant goodbye to a father who was unable to see his son grow up.”

Although Ashley never got to know his father, he says that in some respects it has shaped the person he is today. “Growing up I didn’t feel like I had a proper family which is why I wanted to have a family myself and I’m lucky that I’ve got one. We’re very close knit. There’s me and my wife Anne, my two daughters and four grandchildren.”

The artist, who turns 80 later this year, is still working – he does drawings for his sketchbooks and finished a couple of paintings during lockdown. And the spirit of his father, he says, is never far away.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I still think of him all the time. It’s stayed with me and I’ve had that feeling that he’s been with me all my life, it’s never gone away.”

Relief among the Allies as the war finally comes to an end

After days of rumour and speculation, the United States President Harry S Truman announced that the Japanese had surrendered to the Allies, ending almost six years of war. He later told a crowd outside the White House: “This is the day when fascism finally dies, as we always knew it would.”

In Britain, Labour’s new Prime Minister Clement Atlee confirmed the news, saying that “the last of our enemies is laid low”.

In an address to the nation, King George VI said: “Our hearts are full to overflowing, as are your own. Yet there is not one of us who has experienced this terrible war who does not realise that we shall feel its inevitable consequences long after we have all forgotten our rejoicings today.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEditor’s note: first and foremost - and rarely have I written down these words with more sincerity - I hope this finds you well.

Almost certainly you are here because you value the quality and the integrity of the journalism produced by The Yorkshire Post’s journalists - almost all of which live alongside you in Yorkshire, spending the wages they earn with Yorkshire businesses - who last year took this title to the industry watchdog’s Most Trusted Newspaper in Britain accolade.

And that is why I must make an urgent request of you: as advertising revenue declines, your support becomes evermore crucial to the maintenance of the journalistic standards expected of The Yorkshire Post. If you can, safely, please buy a paper or take up a subscription. We want to continue to make you proud of Yorkshire’s National Newspaper but we are going to need your help.

Postal subscription copies can be ordered by calling 0330 4030066 or by emailing [email protected]. Vouchers, to be exchanged at retail sales outlets - our newsagents need you, too - can be subscribed to by contacting subscriptions on 0330 1235950 or by visiting www.localsubsplus.co.uk where you should select The Yorkshire Post from the list of titles available.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf you want to help right now, download our tablet app from the App / Play Stores. Every contribution you make helps to provide this county with the best regional journalism in the country.

Sincerely. Thank you.

James Mitchinson

Editor

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.