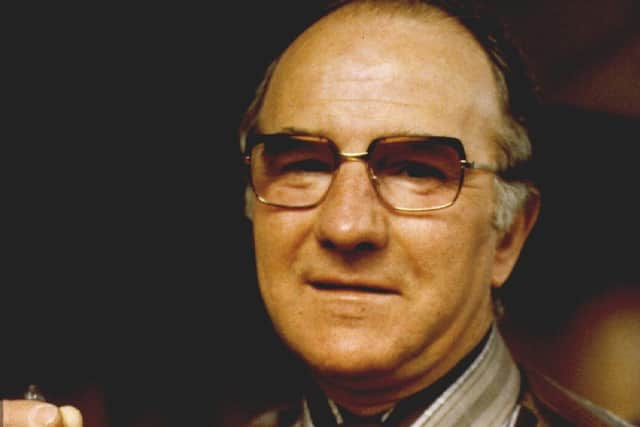

How University of Hull chemist George Gray's creation made LCD flat-screens viable

LCD screens became a ubiquitous part of daily life but the work of Prof Gray, who died in May 2013, has been credited with first making them so.

In early 1970s, he created a new chemical compound in a University of Hull laboratory. His new liquid crystal molecules - known as 5CB - made liquid crystal displays (LCDs) “viable” and consequently gave rise to the enormously lucrative colour flat-screen industry.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile the creation initially made the displays on digital watches and calculators possible, his breakthrough has since been developed for devices we take for granted today, like laptops and mobile phones.

Mark Lorch, Professor of Public Engagement and Science Communication at the University of Hull, explains that liquid crystals are a kind of fourth state of matter, existing between a liquid and a solid.

"At one time something like 90 per cent of the liquid crystal displays - LCDs - all over the world contained George Gray's molecules,” he says, but adds the distinction is that “he didn’t invent the liquid crystal display, he created the molecules that are integral to the display”.

The story begins with Mr Stonehouse, who in 1967 was Minister of State for Technology.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt had been suggested to him - whether correctly or not - that the UK was paying the Americans more for the rights to use their colour cathode ray tube technology (the type seen in bulky televisions and monitors) in displays used by the military than it was on developing Concorde.

Mr Stonehouse was therefore convinced the UK needed to develop its own colour flat-screen panels and so instigated a government working group, led by the physicist Professor Cyril Hilsum, to make it happen. It met with experts in various fields to decide which technologies should receive funding, and liquid crystals was one area up for consideration.

Prof Gray – who later became a CBE and achieved the 1995 Kyoto Prize in Advanced Technology – bagged Hull the contract after a brilliant intervention at an awkward moment in the meeting.

Professor Hilsum, as cited in a biographical memoir on Prof Gray for the Royal Society by former colleagues John Goodby and Peter Raynes, recalled that the meeting was hearing from a person then regarded as the UK authority on liqiud crystals.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the end of the talk Prof Hilsum called for questions but there were none and tried to fill the gap by asking about a reflection made by the speaker’s liquid crystal sample.

Prof Hilsum recalled: “He attempted an explanation, realized this was wrong, remembered a reference to the phenomenon in a book he carried, rapidly turned the pages of this book, decided that the reference was in his loose notes, upended these, dropped both the notes and the book, and then knelt on the floor picking up the pieces.

“The meeting was rapidly escaping from my control when a quiet voice from the back of the room said ‘I wonder if I can help’. I lifted my eyes from the grovelling body of my key speaker and replied ‘I’d be most obliged if you would’, and my rescuer proceeded to give a succinct explanation. That was the first time I met George Gray.”

Scotland-born Prof Gray’s work started, alongside researchers John Nash and Ken Harrison, in Hull in October 1970 and 5CB was made in 1972. Fifty years ago today, they outlined the science in a paper for the Electronics Letters publication.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdExplaining some the science, Prof Lorch says: “He added this molecule that (meant) you could change the properties of the liquid crystal by applying an electric field to it. So you could turn it from interacting with light to not interacting with light. And that meant that by applying an electric field to the liquid crystal and this display you could turn pixels from being dark to light. And that is fundamentally what you see in a calculator or on a modern screen. You're seeing a liquid crystal, when it goes dark, when it goes black, you've stopped the light coming through the display. When you turn it on and it goes light, you've changed the structure of the liquid crystal within the display, and now allows light through.”

The molecule is known as 4-Cyano-4’-pentylbiphenyl (5CB for short).

Prof Goodby says 5CB allowed all of the devices of that era to work at room temperature, and therefore it made viable the commercialisation of flat displays.

Shortly afterwards the first devices containing the compound, such as calculators and digital watches, were on sale.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut Prof Lorch says that later colour screens work on the same principle, except each pixel is made from three tiny sub-pixels, with red, green and blue filters added to the layers. These can be controlled individually to generate the millions of hues we see in modern high-resolution screens.

Prof Raynes invented technologies including the LCD used in the first generation of mobile phones and laptop computers.

Some of the first colour flat-screen TVs hit the market when the Sharp Corporation launched its 14-inch LCD television in 1988 – the same year that Mr Stonehouse died.

As for George Gray, though, Prof Lorch says: “He's well known in certain circles, but he's certainly not very well known publicly and people, when I'm out and about, people ask me: ‘Oh what’s the University of Hull well known for?’ When I tell them liquid crystal molecules, they're stunned that they weren't aware of that as being something that came out of Hull.”