Battle for coal that changed Yorkshire forever

As the wife of a striking Yorkshire miner, she was struggling to feed her family, but also proud of the stand the National Union of Mineworkers was making against pit closures. Today, as a lecturer at Hull University Business School, she still believes the sacrifice was worthwhile, despite the fact that her family had no income for a year, and it took two years to clear their debts.

“Every other family involved had the same experience,’’ she recalled. “Afterwards, I decided that we should never again be as vulnerable. It led me to return to education as a mature student.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMs Thursfield’s life, like many others, was never the same. Today, as a lecturer in organisational behaviour and human resources management, she believes the strike marked a watershed in industrial relations history.

She said: “Despite the outcome, it was worthwhile and I am incredibly proud to have been a part of it. I know of very few miners or miners’ wives who would disagree with me on that.”

Since the strike, the skilled manual jobs that provided work for tens of thousands of people, and paid a reasonable wage, have largely disappeared, according to Ms Thursfield.

She said: “My community suffered in the way that many communities suffered. It went through a process of de industrialisation and a shift from stable, reasonably paid and secure jobs, to a generally low-paid service economy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The UK economy has a large number of well-paid professional and white-collar jobs and a large number of low-paid, insecure flexible’ occupations, for example, zero-hours and short-hour contract jobs. At the start of the strike, the NCB (National Coal Board) said that the closure programme was limited. Arthur Scargill (NUM president) claimed that 70 mines would close. In 1984, there were over 200 coal mines. There are now three.”

What is left of the British coal industry has struggled to break even in recent years because of rising costs, hefty pension liabilities and competition from cheap imports. Last year, Richard Budge, a mogul who once had the nickname King Coal, was declared bankrupt.

Mr Budge bought British Coal from the Government through his company RJB Mining for £814m in 1994. Yorkshire has witnessed decades of pit closures, and the shut-down of Maltby Colliery near Rotherham last year means there are now just two active deep mines left in the region – at Kellingley Colliery in North Yorkshire, and Hatfield Colliery near Doncaster.

Last July, a deal to save up to 2,000 jobs at eight UK coal mines, including Kellingley, was secured, to the relief of the communities they served. UK Coal, which operates deep mines at Kellingley and Thoresby in Nottingham, announced that two of its companies had gone into administration. UK Coal Mine Holdings and UK Coal Operations’ assets are now held in individual companies owned by a new business, UK Coal Production. The restructuring plans have seen the remaining mines taken over with the backing of Britain’s pension rescue scheme, The Pension Protection Fund (PPF).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to Ms Thursfield, coal mining cannot be sustained in a “short-termist” market culture.

She added: “If the industry had the degree of state support given to alternative energy industries, the outlook might be more promising.”

David Parry, of the Industrial Communities Alliance, which campaigns on behalf of industrial areas in England, Scotland and Wales, said: “The decline of the British coal industry was inevitable, but not at the pace it was carried out or to the extent of the run-down.

“The decision to destroy the industry was more political than economic. Coal, in the winter months, provides around 50 per cent of electricity supply. In recent years, coal’s use has gone up. There is still a market for around 60m tonnes per year in the UK. But UK production is only about 17m, and rapidly falling, with the closure of Daw Mill (in Warwickshire) and problems in Scotland with opencast.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There is a lot of cheap coal on the international market, partly as result of shale gas production in the US. With a commitment to indigenous coal production, in places like Yorkshire, this would not have happened so catastrophically, and the UK’s coal assets would have been managed much more sensibly in a balanced energy market.

“Use of coal will fall over time but it should be part of the solution, not the problem for reducing carbon emissions.”

Greater use of carbon capture and storage would provide a future for coal and other fossil fuels, says Mr Parry. He added: “Yorkshire and the Humber would be well placed to develop carbon capture and storage. It would benefit not only the coal industry, but the power generators in the Aire valley (in West Yorkshire) as well steel works and chemical works long-term.”

“Successive Governments have fudged and delayed. Clean coal technology has been around for decades but never deployed in the UK. It has been a very long tale of lost opportunities.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKeith Laybourn, a history professor at Huddersfield University, whose father Donald was a miner, also believes that Britain needs a co-ordinated energy policy.

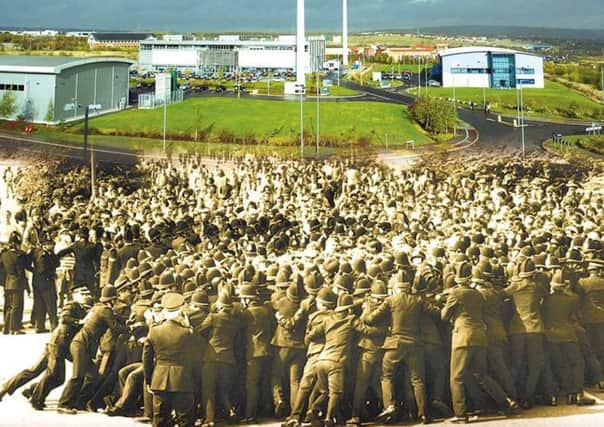

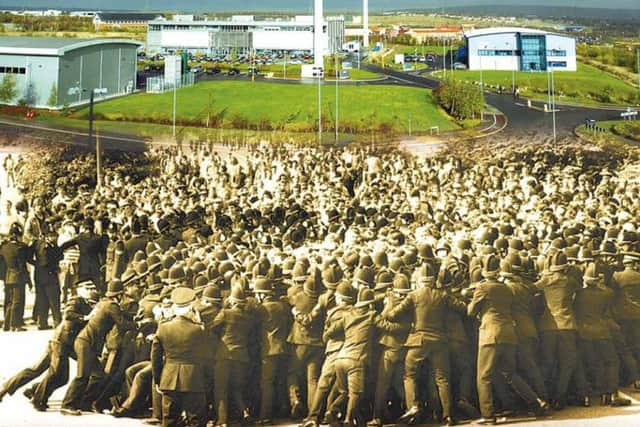

Some former mining land has been re-developed to create hi-tech jobs. The Advanced Manufacturing Park (AMP) in Rotherham, stands close to Orgreave, a place synonymous with the miners’ strike. Police clashed with pickets at the “Battle of Orgreave”, in one of the dispute’s most notorious incidents.

The coking plant and colliery at Orgreave were victims of the downturn of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The AMP was created in a joint venture between the former regional development agency, Yorkshire Forward, and UK Coal, the land’s owner.

At its hub, the AMP has some of the world’s leading materials and research organisations, including the University of Sheffield Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre with Boeing (AMRC), and the new Nuclear AMRC. More than 700 people are employed at AMP, many in technical and research posts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMr Parry said: “It is very welcome that there has been economic development on coalfield sites, and good job opportunities are still around for some at AMP. No one wants to live in the past. However, many of these places still struggle, and much more needs to be done.”