Art at the coal face

As he greets me at Castleford Station, Harry Malkin looks more Left Bank than West Riding. He’s sporting a pointed beard and a rather stylish tweed cap. It’s the look of an artist – a successful one at that, and deservedly so. But the accent is still broad Yorkshire and the commitment to commemorate the considerable mining heritage of this area undimmed by the passage of time. “Nobody else is going to do it,” he says as we set off towards the nearby village of Fryston where he worked underground from 1966 when he was 15 to 1985 when the colliery closed two days before Christmas and not yet a year after the end of the miners’ strike.

He had been a fitter, maintaining and repairing heavy machinery in the cramped spaces of low seams. His father, also Harry, as he was known at the pit, played a part in the development of the precocious artistic talents of Young Harry, as a piece I wrote for the Guardian’s art pages back in 1998 made clear.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Many an artist has drawn on his father’s influence. Perhaps only Harry Malkin has drawn on his father’s back. It was a broad back. ‘As big as a barn door,’ he recalls. Malkin senior was a miner who worked almost naked at the coal face. When he came home, he liked to lie full length in front of a coal fire with his shirt off. Young Harry, who was eight or nine at the time, would set to with his Biro. Cartoons first, then eagles, dragons and other exotic creatures were inscribed like temporary tattoos.”

You may be wondering why he didn’t use a drawing pad instead. Well, it seems that paper was as rare as leather-bound first editions in some mining villages. I remember Harry telling me that he and his brother and sister were always fighting over scraps of discarded wallpaper. For him the pad came later. First he used to scribble caricatures to amuse the lads underground at ‘snap-time’. He used Biro at first, then pencil. But it was the switch to charcoal that imbued his work with the depth and tone that best suited his subject matter.

By that time the pit had closed and he could finally stand back and try to put a meaning ot the vivid memories he had of what he and his workmates had been doing in those low seams. He wouldn’t be the first professional artist to emerge from such a background. Far from it. Collieries have a long tradition of producing what you might call miner-artists. The Ashington Group from the 1930s have been celebrated by the touring National Theatre production of Lee Hall’s The Pitmen Painters. Less well known is the Spennymoor Settlement, which helped develop the considerable talents of Norman Cornish and another Durham man, Tom McGuinness.

Harry’s first exhibition started in a cafe in Pontefract in 1986 – “somewhere between the serving hatch and the gents”, as he puts it. Yet somehow it finished up at the Royal Festival Hall where it ran for three months instead of the expected three weeks. Every picture sold at the end of the first week.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen we reach Fryston it’s very different from the scene that I remember from my last visit in 1998. Instead of ponies grazing on the greyish grass in the shadow of landscaped spoil heaps there is a new village green, funded by English Partnerships as part of an ongoing regeneration project and designed by the American landscape architect Martha Schwartz.

The green is threaded with pathways and low stone walls. There’s a stone sculpture too which looks like a giant finger pointing skyward, as well as the obligatory model of a pit winding wheel and some wrought iron bollards by Antony Gormley no less.

It’s all very tasteful and easy on the eye. What the green lacks is much in the way of life. Admittedly it’s Friday morning and the swings in the children’s playground are stirred by nothing more than a stiff breeze. The kids are at school, albeit in another village. Harry sighs: “The school here went long ago. So did the shops. This used to be a thriving village with a chip shop and a chapel, a newsagent’s, butchers and Co-op.”

It helped of course, that almost a thousand miners might be coming and going on one shift or another.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“A lot of them lived here when I started in the 1960s,” Harry recalls. Others came from Castleford or adjoining villages. The Malkins came from Airedale about a mile away, and the young Harry made various attempts on the four-minute mile on those occasions when he woke up five minutes before the six o’clock buzzer signalled the start of his shift at ear splitting volume.

“I could run a bit in those days,” he smiles. “We had a greyhound and I used to try to keep up with it when it was my turn to take it out.”

Part of Harry misses the bustle of Fryston and the “crack between the lads” – the bleak humour of men working in hot, low seams about a mile underground.

Harry stayed out through the full 12 months of the miners’ strike in the fight to keep the pits open. He knew full well that there would be few alternative sources of employment in an area like this that would pay a living wage. “A lot of it’s security work; 50 bob and bring your own dog.”

On the other hand…

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I wouldn’t want to go back. Not a chance. My dad retired through ill health at 62, the age I am now. He had pneumoconiosis [dust on the lungs] whereas my life has been transformed over the past 20 years.” He knows full well that’s because he had a special talent that was recognised at a key stage. And he’s also well aware that there are plenty of former miners still “sitting around watching daytime television”, as he puts it. “One of them came up to me when we putting up The Cage and said, ‘Do you know what? I’d got back down t’pit tomorrow.’”

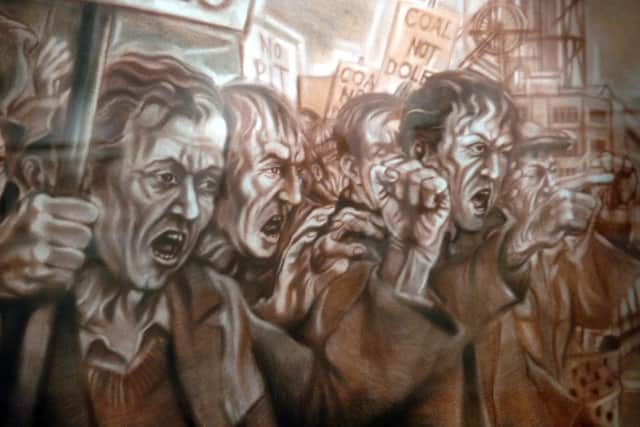

The Cage is one of an increasing number of Malkin sculptures on an impressive scale. Mounted on a plinth, it stands some 14ft high – a great clay cube engraved with pre-war miners crammed into a winding cage on one side, strikers matching with banners on another, roof supports being erected on the third and a rodway drilling machine of the kind that Harry once serviced on the other.

It also stands on another village green. This one is at Allerton Bywater, where the local colliery closed in 1992. Near the former pithead stocks and on the edge of the green is a selection of new Barratt Homes, some of which wouldn’t look out of place in Amsterdam. We’re only just eight miles from Leeds and it’s not too difficult to see the appeal for would be commuters of houses starting at less than £100,000 for two bedrooms.

Across the main road is another sign of the times. Where a working man’s club used to stand is now the Samuel Valentine Urban Food Hall, offering a selection of fine wines, the products of Yorkshire micro-breweries, a range of local cheeses and cooked meats.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe’re joined by Steve Lane, former Fryston face-worker who became rather better known as a rugby league stand-off. He scored well over 100 tries in a career spanning 17 years. Today he’s a petroleum broker.

“I used to get up at five for the early shift, leave between 1 and 2pm and drive all the way to Whitehaven for a 7.30pm kick off. I’d get in at 3am, get two hours’ kip and then walk a mile to the coalface.”

So what did Steve think working in the pits had given him? “Character,” he says without hesitation. “Fryston was full of characters. And comedians.” Harry nods happily. I don’t need to ask what working at the pit gave him. But would he have become the respected artists that he is today without the chance to develop his technique on the rich canvas of his father’s broad back?

Britain’s Lost Mines by Chris Arnot is published by Aurum priced £25. To order from the Yorkshire Post Bookshop call 01748 821122.